AVIATORS’ CERTIFICATES (‘TICKET’ OR ‘BREVET’)

BACKGROUND

Edward Wakefield was elected as a member of The Royal Aero Club (‘RAeC’) on 1 March 1910.

‘The Aero Club of the United Kingdom is to be regarded as the paramount body in all matters of sport and the development of the art of aeronautics.’ – Flight magazine, 8 May 1909.

Founded in 1901, the Aero Club began issuing Aviators’ Certificates on 8 March 1910, recognised internationally by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (‘FAI’) established in 1905. The 8 founding member countries of the FAI were represented by: L’Aéro-Club de France, Der Aero-Club der Schweiz, The Aero Club of the United Kingdom, L’Aéro-Club Royal de Belgique, La Società Aeronautica Italiana, Deutscher Luftschiffer-Verband, The Aero Club of America, and El Real Aeroclub de España.

In anticipation of engine failures, Certificates carried a request for aid and assistance in French, English, German, Spanish, Italian and Russian.

The Aero Club was granted a Royal prefix on 15 February 1910, announced in Flight magazine sent free of charge to members. It is still the UK representative on the FAI the world air sports federation, albeit pilot licences and ratings have been issued by the Civil Aviation Authority since 1972.

Also, ‘The Aeronautical Society of Great Britain [founded in 1866], which is the oldest institution of its kind in the world, is to be regarded as the paramount scientific authority on aeronautical matters, and is to be consulted on all questions dealing with scientific phases of the movement’. – Flight magazine, 8 May 1909. A Royal prefix was granted in 1918 and it became the Royal Aeronautical Society (‘RAeS’). The RAeS is now the only professional body dedicated to aerospace, aviation and space communities.

1909

The origins of Waterbird were in 1909

The first British Aero Show was held 19-27 March at Olympia, London. It was organised by the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders Ltd with the support of the Aero Club. New to the market was the 50 horse power Gnome rotary engine at a cost of £400, exhibited by Gauthier and Co: this photograph is from Flight magazine, 10 April 1909. – Waterbird was built by A. V. Roe & Co (‘Avro’) and fitted with a Gnome engine. Flight-testing as a landplane took place at Brooklands in 1911 by ‘Freddie’ Raynham, witnessed by Howard Pixton who was Avro’s chief instructor.

The world’s first international air race was held on 28 August at Reims, France for the Coupe Internationale D’Aviation presented by Gordon Bennett. In attendance were Roger Wallace, chairman of the Aero Club, Lord Northcliffe, representing the British press, David Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer, and the chiefs of staff of the British Army. Word came to the winner Glenn Curtiss that the United States naval attaché in Paris had sent a favourable report on what he had seen: ‘The aeroplane will have a usefulness in naval warfare’. Curtiss returned home intent on converting a landplane to take off and land on a warship, or, if fitted with floats, to take off and land on water. – Waterbird was an Avro Curtiss-type.

On 7 August, Roger Sommer had established the world endurance record. At Reims on 29 August, Gertrude Bacon flew as a passenger in Sommer’s Farman. At Windermere on 15 July 1912, she became the first woman in the world to fly as a passenger in a hydro-aeroplane. An accomplished balloonist, she had been elected as a member of the RAeC on 10 May 1910.

On 18-20 October, Wakefield attended the Blackpool Aviation Week, which was recognised by the RAeC thus being the first British official air show. Independently of Curtiss, he there put forward the concept of flying from water, but was ridiculed by the experts present.

Wakefield and Curtiss shared the motivation that landing on water would be safer and that such aeroplanes could be used for military scouting.

L’AÉRO–CLUB DE FRANCE

‘The French Aero Club has formulated the regulations under which it will issue its Pilot Aviator Certificate. Candidates must have accomplished three closed circuits of at least 1 kilometre in length, and the trials must be made without a passenger, on different days, and all within a month.’ – Flight magazine, 30 January 1909.

L’Aéro-Club de France (‘l’AécF’) began issuing Aviators’ Certificates from 1 January 1910. Licence No. 2 was issued retrospectively to Curtiss on 7 October 1909 and the first 16 were granted in alphabetical order to those who had already demonstrated their abilities. No. 29 was issued to Sommer.

‘If one wished to fly – and had the money, you went to France, bought a machine, receiving a certain amount of instruction on it. The French, to say nothing of the Wrights, were several years ahead of us at that time.’ – The Brooklands Story A. V. Roe & Company 1910/11 by Howard Pixton. Such a person was Graham Gilmour, who obtained Licence No. 75 at Pau on 19 May 1910 and purchased a Blériot XI. Also, John Porte (later Lieutenant Colonel, CMG, FRAeS) was awarded Licence No. 548 at Reims on 28 July 1911, flying a Deperdussin, who became a flying boat pioneer.

By 28 July 1911, the RAeC had only issued 106 Aviators’ Certificates, in contrast to the 548 by France.

Gertrude Bacon’s second flight in an aeroplane had been with Gilmour in 1910 at Brooklands.

‘We dare venture the opinion that were Windermere in France, not only would there be no agitation, but that money, both public and private, would be offered freely for the helping forward of serious and useful experiment.’ – Flight magazine, 27 January 1912.

‘The question of issuing a Special Certificate for pilots of hydro-aeroplanes has been considered and it has been decided to issue a temporary brevet and in the meantime to refer the matter to the next Conference of the FAI.’ – Flight magazine, 14 September 1912. The request for an extraordinary Conference was supported by the RAeC. At the Conference on 28 January 1913, it was decided to institute a Special Certificate. – Flight magazine, 1 February 1913.

THE RAeC AND THE FAI

‘Letter from the Aéro-Club de France, of 17 February 1912, intimating that they had not granted any Aviators’ Certificates [Brevet de Pilote] for flights carried out on hydro-aeroplanes, and that, in their opinion, the present rules did not cover such an event, was read and noted. It was unanimously resolved to give notice to the FAI that the RAeC would raise the question at the next [FAI] Conference.’ – Minutes of Executive Committee meeting of the RAeC, 20 February 1912.

‘Letter from Capt. E. W. Wakefield of 21 February 1912, with regard to Hydro-aeroplane Certificates, was read. It was unanimously resolved [taking the opposite view to France] to grant provisional Certificates in respect of tests carried out on hydro-aeroplanes, such Certificates to be subject to confirmation by the FAI, the tests being the same as those required for the present Aviators’ Certificates, subject to modification regarding the alighting on water.’ – Minutes of Executive Committee meeting of the RAeC, 27 February 1912.

‘At the FAI Conference held in Paris on 15 and 16 March 1912, the suggestion of the RAeC that Aviators’ Certificates should be issued in respect of flights made on hydro-aeroplanes under the existing rules was adopted, pending special regulations to be approved at the Vienna Conference in June next.’ – Minutes of Executive Committee meeting of the RAeC, 19 March 1912.

Aeroplane Certificates recognised by the FAI up to 31 December 1912, with figures at the beginning of 1911 in brackets, were:-

France 966 (353)

United Kingdom 376 (57)

Germany 335 (46)

United States 193 (26)

Italy 186 (32)

Russia 162

Austria 84 (19)

Belgium 58 (27)

Switzerland 27

Holland 26

Argentine Republic 15

Spain 15

Sweden 10

Denmark 8

Hungary 7

Norway 5

Egypt 1.

Wakefield accompanied the representatives of the RAeC, Griffith Brewer and Harold Perrin, to an Extraordinary Conference of the FAI held in Paris on 28 January 1913 .‘The FAI decided that the ordinary Aviators’ Certificates should be valid for flights over both land and water. It was further decided that Certificates should be granted in respect of tests made over the water, but that such Certificates should not be valid for flights over land. It will therefore be seen that it is not necessary for the holders of the FAI Aviator’s Certificate to obtain a special water Certificate. In the case, however, of aviators who have passed the water tests only, their Certificates will be endorsed accordingly, and do not imply qualification for land flights. The holder of a Certificate so endorsed can have it converted into a full FAI Aviator’s Certificate, on carrying out the landing tests at present in force.’ – Minutes of Executive Committee meeting of the RAeC, 4 February 1913.

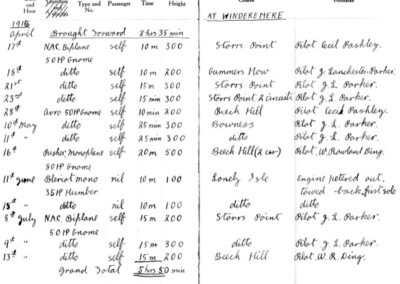

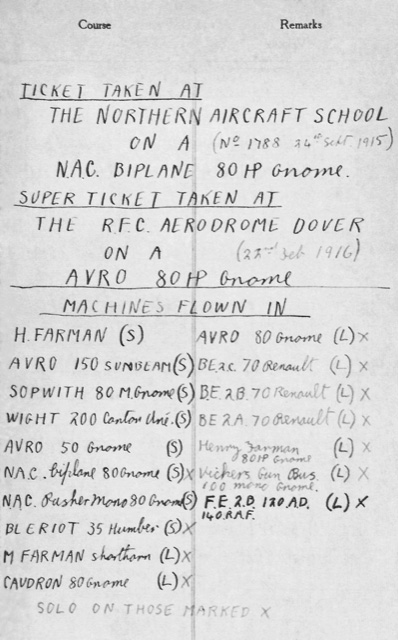

An illustration of the above conditions can be seen in the documents of Donald Macaskie. Macaskie’s log book of civilian flying – extract at the foot of this page – records that he flew in the entire Windermere fleet, as it then was, of Waterhen, Seabird, the Lakes Monoplane and a Blériot. His tests were accomplished on Waterhen 4-22 September 1915, at the age of 19, with a total time flown 0f 9 hours and 30 minutes. One of his instructors was John Lankester Parker, who had been awarded his Certificate at Brooklands on 18 June 1914 and also held a Competitor’s Certificate for 1914. Parker became Chief Test Pilot for Short Brothers 1918-1945.

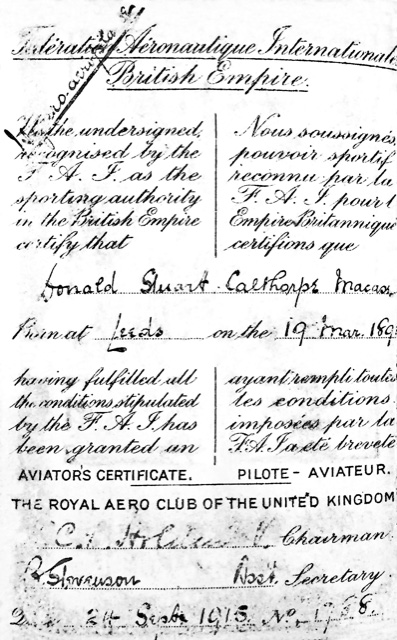

The extract from Macaskie’s Aviator’s Certificate No. 1788 at the foot of this page, issued on 24 September, carries at top left the diagonal handwritten endorsement of ‘Hydro-aeroplane’, meaning he was only licensed to alight on water. His index card at the RAeC was therefore headed ‘Hydro-aeroplane’. On the other hand, Parker had obtained his Certificate on land which qualified him to fly from water so his Certificate was not so endorsed.

Macaskie transferred to the Royal Flying Corps and so would need to re-take his tests on land. He did so at RFC Dover aerodrome, as part of his RFC pilot training. By this stage of World War 1 the military was conducting flying tests as well as the RAeC. The summary in his log book of military flying at the foot of this page, shows that on 22 February 1916 he was awarded what he called a ‘Super Ticket’, as it converted his Certificate so as to qualify him for both water and land.

The term seaplane was coined by Winston Churchill on 17 July 1913, when as First Lord of the Admiralty he answered a question in the House of Commons.

‘Some time ago there was a discussion at the FAI on the subject of the sphere of activity that should be covered by the various Aero Clubs affiliated under the Federation. A suggestion that this sphere of activity should be enlarged to take in science and industry was opposed by the British and French delegates; and we think, rightly opposed. In this country we have the RAeC for science and the Society for British Aircraft Constructors for manufacturers.’ – Aeronautics magazine, 29 January 1920.

THE RAeC AND THE AIR MINISTRY

An illustration can be seen in the documents of ‘Freddie’ Raynham, who test-flew Waterbird as a landplane at Brooklands on 1 July 1911. He held RAeC Certificate No. 85 granted on 9 May 1911 and on 23 September 1919 was issued with private Licence No. 317 by the Air Ministry.

An article in Flight magazine, 21 April 1927 ‘How to Obtain Your Private Licence’ explained the requirements for an “A” Licence by the Air Ministry route. That is, to produce evidence of medical fitness, competency and recent flying experience. If an RAeC Certificate issued since 31 October 1922 was held, then there was exemption from both a practical flying test and a technical examination for a private pilot’s licence, whilst the fee was reduced from 10 shillings to 5 shillings. If the RAeC Certificate was issued between 1 February 1920 (see Regulations at the foot of this page) and 31 October 1922, or the applicant was qualified in the RAF, the exemption was from only the practical flying test. The technical examination was conducted orally at the Air Ministry. If there was no ‘recent flying experience’ i.e. 3 hours’ solo within a year, the applicant would have to do 3 figure-of-eight turns and 3 landings, stopping on each occasion within 50 yards from a certain point.

The last RAeC Certificates were issued in 1956.

THE AERO CLUB OF AMERICA

The first tests taken on a hydro-aeroplane under the Aero Club’s standards, based on those of the FAI, were completed on 2 July 1911 by Lieutenant Theodore Ellyson who was licensed No. 28.

At a dinner of the Aero Club on 27 January 1912, it was stated by the French Ambassador that in France there were 800 air pilots making daily ascents, while there were only 90 in the United States. – The New York Times, 28 January 1912.

The Navy’s fourth pilot was Ensign Victor Herbster who obtained Certificate No. 103 on 28 February 1912. He was one of only 2 pilots ever issued a license on the basis of all flights on water. – Wings for the Fleet by G van Deurs. Whilst the RAeC operated the system of endorsing Certificates ‘Hydro-aeroplane’, the Aero Club instituted 421 numbered special Certificates for brevetting ‘Hydraaeroplane’ pilots. Certificate No. 1 was granted to Adolph Sutro on 19 February 1913. It is intriguing that this letter to Sutro from the Secretary of the Aero Club refers to a Hydroaeroplane Certificate, yet Hydraaeroplane Certificates were actually issued.

On I January 1914, Ellyson was the first to qualify as a Navy Air Pilot, with Herbster fifth.

The American Magazine of Aeronautics, 15 October 1914 reported on what was believed to be first time the US government had penalised an aviator. Dean Vankirk of Washington was fined concerning his flying boat for navigating after sunset, running without lights, insufficient life saving devices aboard and not having copies of the pilot rules aboard.

The first private License was issued by the Department of Commerce on 6 April 1927.

CERTIFICATE FIRSTS

- France: Louis Blériot on 7 January 1909 and Raymonde de Laroche No. 36 on 8 March 1910 the first Certificate issued to a woman

- Belgium: Pierre de Caters on 2 December 1909 and Hélène Dutrieu No. 27 on 25 November 1910 the first woman to fly a hydro-aeroplane on 30 June 1912 in a Farman over Lac d’Enghien, France

- Denmark: Robert Svendsen on 15 January 1910

- Germany: August Euler on I February 1910 and Amelie Beese No. 115 on 13 September 1911

- United Kingdom: John Moore-Brabazon on 8 March 1910 and Hilda Hewlett No. 122 on 29 August 1911

- Russia: Mikhail Efimov on 21 March 1910 and Lydia Zvereva No. 31 on 22 August 1911

- Austria: Adolf Warchalowski on 22 April 1910

- Italy: Mario Calderera on 10 May 1910 and Rosina Ferrario No. 203 on 3 January 1913

- Sweden: Carl Cederstrom on 27 June 1910 and Elsa Andersson on 30 June 1920

- Spain: Benito Loygorri on 30 August 1910 and Maria Bernaldo de Quirós in October 1928

- Switzerland: Ernest Failloubaz on 1 October 1910 and Else Haugk No. 48 on 11 May 1914

- Hungary: Ágoston Kutassy on 22 December 1910 and Lilly Steinschneider No. 4 on 15 August 1912

- United States: Glenn Curtiss on 8 June 1911 who had made the first ‘practical’ hydro-aeroplane flight on 26 January 1911 at San Diego Bay, California and Harriet Quimby No. 37 on 1 August 1911

- Holland: Johan Hilgers on 12 August 1912 and Beatrix de Rijk No. 652 (France) on 6 October 1911

- Norway: Roald Amundsen on 11 June 1914 and Dagny Berger No. 8160 (United Kingdom) on 27 September 1927.

WINDERMERE

‘Waterbird provided the vital springboard to establishing a twin centre of technical innovation and flying expertise.’ – Navy Wings

The first British hydro-aeroplane school was established by The Lakes Flying Company in 1911. This advert is from the RAeC Year Book 1914.

The Admiralty took an early interest in training pilots at Windermere. ‘Bristol school or Wakefield hydro-aeroplane school to train those pilots that cannot be received at Eastchurch at present.’ – Recommendation in a Paper entitled ‘The Development of Naval Aeroplanes and Airships’ dated 23 January 1912, by Rear Admiral Ernest Troubridge, Chief of Staff of the Admiralty.

The first full Aviator’s Certificate with the RAeC tests taken on a hydro-aeroplane was achieved at Windermere by 2nd Lieutenant John Trotter on 12 November 1912. That is, Trotter’s Aviator’s Certificate No. 360 was issued before introduction of the Regulations following the January 1913 Paris Conference, so entitling him to carry out both water and land flights. Note therefore that his index card is not endorsed ‘Hydro-aeroplane’. The official RAeC observers for his tests were Reverend Sidney Swann, a founder member of the Aero Club (9 November 1909), and Major Robert Brocklehurst. Swann, like Wakefield and Oscar Gnosspelius, was inspired by having attended the Blackpool Aviation Meeting in 1909, and carried out experiments at Aintree racecourse, Liverpool and at Crosby Ravensworth, near Shap. Brocklehurst carried out experiments at Eastchurch, and Windermere – the Aeroplane magazine of 10 April 1913 mentioned a hydro-monoplane with bat’s wings in the course of construction.

The first and second Aviators’ Certificates endorsed ‘Hydro-Aeroplane’ awarded by the RAeC were to Windermere-trained pilots. Joseph Bland was granted Aviator’s Certificate No. 614 on 30 August 1913, and Oswald Lancaster No. 765 on 15 April 1914. Note that Trotter’s Certificate carried the date of the RAeC Committee meeting when issued, whereas Bland’s and Lancaster’s Certificates were back-dated to when the tests were passed (which applied to Nos. 453-864).

The system for tests at Windermere was described by Clifford Fleming-Williams in an article for The Royal magazine, January 1916. ‘2 floating marks have been towed out by the motor-boat and anchored 500 yards apart. The motor-boat takes up her position between the two. The aeroplane has climbed well up, passes right over us, and begins a right-hand turn outside one of the buoys. Round she comes, passes directly overhead again and does a left-hand turn outside the other buoy. As she passes over us again the Aero Club Judges mark “1” in their note-books. The student must make 5 such figures of eight, and come to rest on the water not more than 164 feet away from us. He must ascend, reach an altitude of at least 328 feet, and descend from that height with motor cut off, within sight of the judges. He climbs up till he must be at least 1,000 feet. The motor-boat dashes round in a big circle dropping newspapers, which floating on the water make it easier for him to judge the surface. Now for the volplané. He has nosed her down and cut his engine out. He straightens out, shoots along 2 inches above the water and touches it with no perceptible splash.’

The cost of tuition at Windermere was £75 until the Certificate was obtained. For Officers, it was discounted to £52 and 10 shillings upon signing an agreement, and £17 and 10 shillings on finishing tests. Extra practice was £9 for the first hour and £6 thereafter.

The RNAS granted a contract for training pilots in December 1915. The private Seaplane School was taken over on behalf of the Government, and on 3 May 1916 the first flying course under the total control of the RNAS commenced. Amongst that intake were 9 Canadian and 2 American pupils. This photo is of 5 Canadians, including James Cronyn from Toronto – in his uniform of a Captain in the Canadian Infantry, and 1 American. There were 5 more Canadians on subsequent courses.

2 Canadians went on to win the Distinguished Service Cross, and 1 Canadian and 1 American to win the Distinguished Flying Cross.

In May 1916, training at Cockshott and Hill of Oaks became Royal Naval Air Service Unit Hill of Oaks. Large numbers of probationary Flight Sub-Lieutenants were sent to Windermere for basic instruction, most of whom had qualified already on landplanes. They were on the books of HMS President II (an accounting base at Crystal Palace, London), having already undertaken a 5-week course there in drill, navigation, theory of flight, aero-engines and signalling.

In June, the headquarters of the RNAS at Windermere moved from Cockshott to Hill of Oaks, and, with the departure of civilian instructors, the name was changed to Royal Naval Air Station Windermere. Please see the photo at the top of this page. – Note the White Ensign flying. RNAS Windermere continued operations until the end of June 1917.

Aeroplanes used for pupils:-

Lakes Waterhen. Spanned from being used for the first Aviator’s Certificate tests on 12 November 1912 to the last on 16 August 1916.

Lakes Seabird. Also known as the Avro. Changing student pilots was speeded up by a system of doing so without stopping the engine, using motor launch Sarah – this drawing is by Fleming-Williams.

Lakes Monoplane. Also known as the Mono.

Blériot XI. Single seater.

Blackburn Improved Type 1. Also known as the Land/ Sea monoplane. Note the cutouts at the wing roots to improve visibility and that undercarriage skids remain from when a landplane.

Nieuport VI.H (4). RNAS.

F.B.A. Type A (9). RNAS. Only the F.B.A. was a flying boat and where the pilots sat side by side. This 1916 page is from the log book of instructor Henry Reid, an ex-pupil. This photo is of Reid in the front cockpit, with David Robertson and John Lankester Parker behind.

Short 827 (3). RNAS.

Subsequent Certificates, bringing the grand total to 23:-

21/08/1914 Petchell Murray No. 881. Joined RNAS, Flt Sub-Lt. Killed in accident at Central Flying School, Upavon 04/11/1914.

11/02/1915 Ralph Lashmar No. 1076. ‘Mr. Lashmar took an exceedingly good brevet, going up to 940 feet and handling the machine with great confidence and good judgment.’ – The Aeroplane magazine, 17 February 1915. Killed in accident at Isle of Wight 07/09/1916.

30/07/1915 Samuel Sibley* No. 1596.

07/08/1915 Ronald Buck* No. 1542.

24/09/1915 Donald Macaskie* No. 1788.

04/10/1915 Harry Slingsby* No. 1818.

04/02/1916 John Coats No. 2404. Joined Royal Flying Corps, Maj, Air Force Cross.

04/02/1916 Henry Reid No. 2416. Joined RFC, 19 Squadron – in this photo Reid is at the middle row on the right, Aeroplane Experimental Station, Lt.

12/02/1916 David Robertson* No. 2460. 03/06/1916 gave first lesson at RNAS Hill of Oaks.

17/03/1916 Francis MacIntyre No. 2590. Seaplane pilot in RNAS and Royal Air Force.

17/03/1916 Joseph Ridgway No. 2593. Joined RFC, Lt, severely injured 24/03/1917, Distinguished Conduct Medal.

18/03/1916 Noel Lawton* No. 2595. Joined RFC.

02/04/1916 Harry Robinson No. 2694.

06/04/1916 Herman Shaw No. 2702.

06/04/1916 Arthur Salton No. 2703.

14/06/1916 Flt Sub-Lt Paul Gadbois No. 3067. 1st pupil of RNAS Hill of Oaks to be awarded Certificate. Seriously injured in accident at RNAS Calshot 09/07/1916.

15/06/1916 Flt Sub-Lt James Cronyn No. 3095.

21/06/1916 Flt Sub-Lt William Wallace No. 3117. Died following accident at RNAS Calshot 21/07/1916.

23/06/1916 Flt Sub-Lt Victor Bessette No. 3125. Qualified as Curtiss flying boat pilot, RNAS and RAF, Capt, Distinguished Flying Cross.

16/08/1916 Edward Haller No. 3420. Joined RFC, 2nd Lt. Killed in action 03/06/1917.

* For more about these pilots, click here

With ground school on the theory of flight and design, and observation at the workshop of engines and interior construction of aeroplanes, the system for practical tuition of Windermere student pilots was:-

1. Passenger flights to get used to being in the air.

2. Pupil allowed to hold control lever under instructor’s hand.

3. Pupil given free control of lever.

4. Pupil in pilot’s seat given full control of lever and rudder with instructor behind.

5. Solo taxiing to learn control of engine and art of acceleration.

6. Solo take-off to long ‘straights’.

7. Full practice for Certificate.

8. Certificate tests.

Also, a hydroplane was used so as to give students practice in travelling fast over water and judging speeds. It was capable of 40 knots, made from a float previously fitted to the Gnosspelius-Trotter, and powered by a 50hp Clerget engine which Gnosspelius had purchased for his No. 2 hydro-monoplane.

RAeC REGULATIONS FOR TESTS

New Regulations were introduced to provide for hydro-aeroplanes in the RAeC tests, effective 1 January 1914. In the altitude flight a maximum reading aneroid had to be carried. – Flight magazine, 3 January 1914:-

1. Candidates must accomplish the 3 following tests, each being a separate flight:-

A and B. 2 distance flights, consisting of at least 5 kilometres (3 miles 185 yards) each in a closed circuit, without touching the ground or water; the distance to be measured as described below.

C. 1 altitude flight, during which a height of at least 100 metres (328 feet) above the point of departure must be attained; the descent to be made from that height with the motor cut off. The landing must be made in view of the observers, without restarting the motor.

2. The candidate must be alone in the aircraft during the 3 tests.

3. Starting from and alighting on the water is only permitted in one of the tests A and B.

4. The course on which the aviator accomplishes tests A and B must be marked out by 2 posts or buoys situated not more than 500 metres (547 yards) apart.

5. The turns round the posts or buoys must be made alternately to the right and to the left so that the flight will consist of an uninterrupted series of figures of 8.

6. The distance flown shall be reckoned as if in a straight line between the 2 posts or buoys.

7. The alighting after the 2 distance flights in tests A and B shall be made:-

(a) By stopping the motor at or before the moment of touching the ground or water [‘vol plané‘];

(b) By bringing the aircraft to rest not more than 50 metres (164 feet) from a point indicated previously by the candidate.

8. All alightings must be made in a normal manner, and the observers must report any irregularities.

9. Each of the flights must be vouched for in writing by observers appointed by the Royal Aero Club. All tests must be under the control of, and in places agreed to by, the Royal Aero Club.

The RAeC revised the Regulations governing tests for Aviator’s Certificates, including for seaplanes – Flight magazine, 29 January 1920:-

‘(A) A flight without landing, during which the pilot shall remain for at least an hour at a minimum height of 2,000 metres above the point of departure. The descent shall finish with a glide, the engines cut off at 1,500 metres above the landing-ground. The landing shall be made within 150 metres or less of a point fixed beforehand by the official examiners of the test, without starting the engine again.

(B) A flight without landing around two posts (or buoys) situated 500 metres apart, making a series of five figure-of-eight turns, each turn reaching one of the two posts (or buoys). This flight shall be made at a height of not more than 200 metres above the ground (or water). The landing shall be effected by:-

(i) Finally shutting off the engine or engines at latest when the flying machine touches the ground (or water.

(ii) Finally stopping the flying machine within a distance of 50 metres from a point fixed by the candidate before starting.

In each test the candidate must be alone in the flying machine.’

Information about the revision was brought to attention by the Air Ministry announcing that a ‘Notice to Airmen’ had been issued, which Notices were introduced in December 1919.

– Grateful thanks to Andrew Dawrant of The Royal Aero Club Trust for providing copy documents.