Henri Fabre’s Hydro-aeroplane, in the centre, at the Monte Carlo Motor Boat Exhibition in 1911. It was there regarded as both a boat and an aeroplane.

THE HYDROPLANE

‘Hydroplane’, ‘Hydro-aeroplane’ and ‘Step’ are described in an article from The Sphere newspaper of 19 April 1913, and an article from Flight magazine of 24 July 1914, which include sketches. (The term ‘Seaplane’ was coined on 17 July 1913 by Winston Churchill when he first used it in the House of Commons.)

THE CROSSOVER BETWEEN HOW BOATS WERE BUILT TO GO FASTER AND HOW AEROPLANES WERE MADE TO TAKE OFF FROM WATER

CHARLES RAMUS

‘It was a clergyman, the Rev. Charles Meade Ramus, who first suggested the hydroplane. He drew the attention of the Lords of the Admiralty [in a letter dated 8 April 1872] to his experiments and their results for war ships, but the scheme as a whole was abandoned. … The design was essentially a flat-bottomed boat with a step halfway along the bottom. Sir John Thornycroft recognised its possibilities and carried out a great many experiments on the subject.’ – Flight magazine, 22 February 1913. This article was about the 4th International Aero and Motor Boat Exhibition, at Olympia, London, organised by the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders Ltd with assistance from the Royal Aero Club, at which the Aeronautical Society was an exhibitor.

The proposal by Ramus to the Admiralty proclaimed ‘The discovery will at least double the speed of some vessels, and will effect a change in locomotion by sea which has never till now been conceived’.

Models were tried in an experimental tank which was being used by William Froude at Torquay on the Admiralty’s behalf for testing ship models to predict speed and stability. However, the vessel would be one of several thousand tons; it was found that the speed required for such a craft was so great that the idea was considered impracticable. Ramus argued that the experiments disproved some of the theoretical objections raised by Froude in his report to the Admiralty in 1872. The matter was debated in the House of Commons in June 1873.

Details of the design and experiments by Ramus were reported in the Scientific American magazine, 6 June 1874: ‘Experiments with models showed that a vessel [in which the bottom was composed of two parallel and consecutive inclined planes] would, when driven at a sufficiently high speed, rise evenly over the water, so as to skim over it’.

‘Naval officers questioned the value of Froude’s model science, doubting, as they did, that there was a relationship between the behaviour of models in a test tank and ships a sea.’ – Shaping the Royal Navy. Technology, authority and naval architecture, c.1830-1906 by D Legget.

The work by Ramus became generally known when it was republished in the Motor Boat magazine of 22 October 1908. In an article of 12 November 1908, it was commented ‘Of course, since those days, the steam engine has improved out of all recognition, but it has been reserved for the modern internal-combustion engine, and one or two specially-constructed steam engines, to bring the hydroplane within the bounds of practicability’.

‘Experiments in water are sometimes a convenient way of observing the conditions which take place in air. This photo, at the National Physical Laboratory, Bushey House, Teddington, shows a trough, through which water is circulated in order to investigate its effect on a submerged object’. – Flight magazine, 22 May 1909.

An article in the Scientific American, 12 June 1909 set out the results of model hydroplane experiments by Thornycroft, Ramus and Froude. Thornycroft concluded that ‘hydroplanes are closed related to aeroplanes’.

Early in 1912, application was made to the Advisory Committee for Aeronautics by the representatives of the Admiralty and of the War Office for carrying out model tests at the William Froude National Tank to determine the best form of float for use on hydro-aeroplanes. Reports dated November 1912 which detailed work done at the tank, comparing floats with flat bottoms and with a step, and tests in the wind channel at the National Physical Laboratory to determine the effect after rising from water, together with a report on light alloys dated September 1913 were all published in the Committee’s Technical Report for the Year 1912-1913.

‘Experiments in the Unites States have been conducted at the Washington tank. These experiments show conclusively that a flat-bottomed punt shape is the most difficult to raise to the hydroplaning speed.’ – The Engineer magazine, 30 October 1914.

ALBERT KNIGHT

UK Patent No. 17,360 filed on 2 August 1906 by Albert Knight is the first patent relating to stepped hydroplanes. – The Aeroplane magazine, 4 September 1913. The patent was for ‘… a distinct joggle or step being formed in the bottom of the vessel, where the fore and after parts meet. … The joggle or step is not necessarily at right angles to the bottom of the vessel, but it may finish in any approved form’.

In a document sent to the Admiralty in 1909, Knight foresaw that ‘the hydroplane might be with great advantage attached to flying machines … serve the purpose of a carriage for the accommodation of the pilot and machinery and any passengers that the aeroplane may be capable of carrying … the adaptation of wheels for alighting on land is a very minor matter’.

‘A small book, published in 1874, The Polysphenic Ship by Ramus was an appeal to the Government to publish the experiments made by the Admiralty to test the inventor’s proposals. … The reverend gentleman had, it appears invented a new type of boat which he had submitted to the Admiralty, but could get no satisfaction from the Government, thus showing that Governments have not changed in the last forty years. … Ramus never patented his invention.’ – Letter from F M Rogers & Co, patent agents, to the Aeroplane magazine, 11 September 1913.

An article ‘An Extraordinary Coincidence’ in the Motor Boat magazine, 10 December 1908, included that Knight had been unaware of the efforts 30 years earlier by Ramus and Thornycroft. The editorial concluded that ‘… to-day the ties between the hydroplane and aeroplane appear to us indissoluble’.

HENRI FABRE

Henri Fabre made the first flight in a powered marine aeroplane near Marseilles on 28 March 1910. ‘It is designed with the greatest care and made like a masterpiece.’ – Gabriel Voisin, who had made the first take-off in a water glider from the River Seine in 1905.

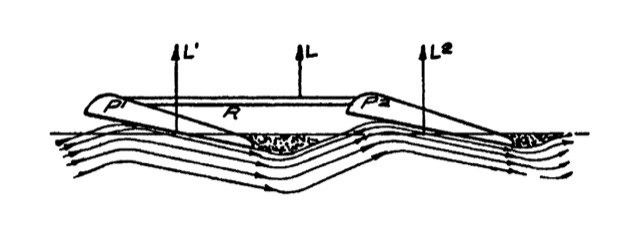

The floats were not stepped, but arranged with the flat part underneath and a curved upper surface, so as to generate lifting force when moving either over water or in the air. ‘The front plane has been completely separated from the rear plane, each forming the bottom of a separate float. This arrangement has the advantage of giving both longitudinal and lateral stability, while the fact of the rear plane being divided and its halves placed some distance apart takes them out of the disturbing influence of the wake of the forward float.’ – Practical Aeronautics by C B Hayward.

The first diagram above shows Fabre’s design with 2 floats P1 and P2, connected by the bar R.

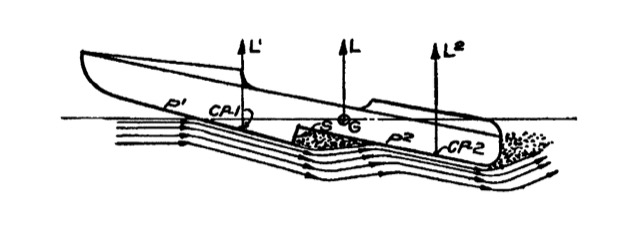

The second diagram above shows a stepped float, the structural difference being that the 2 planing surfaces P1 and P2 are combined in 1 hull. The hull is divided into 2 separately inclined surfaces.

– Motor Boats, Hydroplanes, Hydroaeroplanes, Construction and Operation by T H Russell.

The fabric covering could be ‘clewed’ – rolled up or reefed.

ROGER RAVAUD

In 1910, S. E. Saunders Ltd built an ‘aero motor boat‘ [in this photo the front is at the left] at Cowes, Isle of Wight for Roger Ravaud, intended for entry in both the aeroplane and motor boat contests at Monaco in 1911 and termed an ‘aéroscaphe‘. Testing was carried out in early 1911 on the River Medina at Folly near Whippingham. ‘It was supported at rest on 2 floats above which were short-span lifting surfaces, fore and aft, which must have been intended to support a significant portion of the weight of the craft and thus reduce water drag. Above these was mounted an aircraft-like fuselage with an engine driving a pusher airscrew. … No information on its performance can be traced and it did not appear at Monaco, consequently it must be assumed that the craft was unsuccessful.’ – From Sea to Air: the Heritage of Sam Saunders by A E Tagg and R L Wheeler.

‘Ravaud declared that the bottoms of the floats were (or could be) ‘constituted by blades’, serving to raise the vessel clear of the water.’ – Aeromarine Origins by H F King. – Hydrofoils.

OSCAR GNOSSPELIUS

Oscar Gnosspelius designed and tested floats with a step at Windermere in July 1910, which were built by Borwick & Sons. He had therefore pioneered the first step-hydroplane underside for a float in the world. He began with 2 central floats, but at the end of 1910 switched to a single float which was 5 feet by 12 feet, derived from experience of a 4 feet by 14 feet float.

‘He decided to make a waterplane, for which purpose he investigated hydroplane design and came upon the stepped pontoon described in 1873 by the Rev Charles Ramus in his book The Polysphenic Ship.’ – Shorts Aircraft since 1900 by C H Barnes.

Earlier in the day than Waterbird’s first flight on 25 November 1911, Gnosspelius took off from Windermere in Gnosspelius No. 2. However, having lost control, he overcorrected causing a rapid bank to the right and then to the left, resulting in the hydro-aeroplane turning over, following which a wingtip was damaged and the propeller splintered upon striking the water.

‘Gnosspelius No. 2 was the first British hydro-aeroplane to employ auxiliary wingtip floats as an aid to stability on the water.’ – The History of British Aviation 1908-1914 by R D Brett.

In a move away from the flat bottom of initial floats, Gnosspelius developed the wave-cutting, spray-deflecting, V-shaped float; which is used on every float today. On 12 February 1914, he obtained UK Patent No. 10,801 for a V-shaped construction.

Gnosspelius was employed by Short Brothers at Rochester from 1919, where he was in charge of the Experimental Department until he left in 1925. ‘Towards the end of 1924, 2 important decisions, taken on their own initiative by 2 entirely independent aircraft manufacturers, were to lead to British pre-eminence in civil aviation during the decade that followed. One was by Short Brothers to build their own 350 feet long water channel at Rochester in which to test model seaplane floats and hulls without having to wait for their turn, often much delayed, to use the William Froude Ship Model Tank at the National Physical Laboratory.’ – Shorts Aircraft since 1900 by C H Barnes. It was designed and built by Gnosspelius along with Arthur Gouge.

Gnosspelius also had an interest in motor boats and in 1926 became a member of Windermere Motor Boat Club during its first year.

GLENN CURTISS

Glenn Curtiss carried out his first experiments, following Fabre’s float design, with 3 hydroplanes.

He made the first ‘practical’ flight from water at San Diego Bay, California on 26 January 1911, using a central float which was 5 feet long and 6 feet wide and also a 30 inches long float forward to provide stability.

By 1 February there was a change to a single float, which was 12 feet long, 2 feet wide and 12 inches deep. – This photograph is captioned ‘About to rise from the water.’ – Practical Aeronautics by Charles B Hayward.

These were the dimensions adopted for Waterbird’s float, which was stepped.

The Curtiss float had been designed to ride through waves of the sea, shaped to slant upward, so giving the necessary angle for hydroplaning on the surface of the water. It was flat-bottomed, not stepped.

Curtiss flying boat No. 2, nicknamed the Flying Fish, had a full-length flat underside. However, it would not lift off the water until a step was added to the hull in early Summer 1912.

Curtiss applied on 4 June 1913 for US Patent No. 1,142,754 for a flying boat which was granted on 8 June 1915 [the step is circled in red].

On 18 November 1916, Curtiss Aeroplane & Motor Co applied for a patent for a pontoon float. US Patent No. 1,269,397 was granted on 11 June 1918.

OLIVER SCHWANN

Commander Oliver Schwann (later Air Vice-Marshal Sir, KCB CBE) purchased an Avro D for £700 in June 1911 at Brooklands. Following transportation to Barrow-in-Furness, stepped floats were lashed to the skids. On 18 November 1911, take-off was achieved to just clear of the water, but, upon falling back, the floats were damaged and the port lower wing was smashed. ‘ … the subsequent crash cannot be considered the first water landing even though both pilot and aircraft survived to fly again’. – The Royal Navy’s Air Service in the Great War by D Hobbs.

On 2 April 1912, Sydney Sippe (later Major, DSO OBE FRAeS) succeeded, the first pilot to fly from British seawater. On 18 April, Schwann also achieved success, having passed the tests for his Aviator’s Certificate on 7 April at Salisbury Plain, but his was the last flight at Barrow in the Avro D.

EDWARD WAKEFIELD

Captain Edward Wakefield commissioned a landplane from A. V. Roe & Co, which was converted to a hydro-aeroplane at Windermere where a double-stepped float built by Borwicks was added and the name adopted of Waterbird. Like the craft of Fabre and Ravaud, it was powered by a 50 horse power Gnome engine.

On 25 November 1911, Waterbird made successful flights, which were confirmed in a telegram from the pilot Herbert Stanley Adams. The Motor Boat magazine carried an article on 30 November 1911 which reported on the flights. The hydroplane float was further verified on 27 January 1912 by Lieutenant (later Air Chief Marshal Sir) Arthur Longmore in his report to the Admiralty ©Trustees of the National Museum of the Royal Navy.

On 11 December 1911, through patent agents Arthur Edwards & Co, Wakefield lodged UK Patents No. 27,770 relating to the means for float attachment including rubber bungees to prevent jar when taking off and alighting, and No. 27,771 for a float formed with steps.

No. 27,770 was granted on 12 September 1912.

No. 27,771 was granted following a Court hearing on 18 March 1913 and duly sealed dated 11 December 1911, the object of the invention being ‘to provide an aeroplane with [improved] means for enabling it to alight, float and travel along the surface of water and to rise again therefrom’. Having carried out considerable experiment, Wakefield had thus successfully combined features of construction for the first time, albeit the features were themselves admittedly old.

Further, on 13 November 1913, Wakefield obtained UK Patent No. 18,051 for a float of a seaplane to support its own weight or the greater part of such weight during flight.

Wakefield explored developments of float design and the options in an article in the Aeroplane magazine, 10 April 1913.

THE PHASES OF WATERBIRD’S FLOAT, AS SHOWN IN THE VIDEO CLIP, WERE:

Constructed in May 1911, with the additions of a single step in September, a second step towards the stern in early November, and later a tapering stern i.e. a ‘bustle’ to add buoyancy aft and reduce drag. Markings and filled boltholes reveal that, in the course of testing, the attachment points for the undercarriage were moved by 4 and 6 inches.

On 14 March 1912, Wakefield entered into an Agreement with the Admiralty for floats and undercarriages, or royalties, and to convert Admiralty Deperdussin M1 (a monoplane) into a hydro-aeroplane; which conversion he achieved within 4 weeks from delivery. The Agreement was subject to the Official Secrets Act 1911.

SUMMARY OF THE FIRST APPLICATIONS OF THE STEP TO AN AEROPLANE

As set out in the evidence above, the core developments were:-

- April 1872. The stepped hydroplane was invented by Ramus

- 2 August 1906. Knight applied for the first stepped hydroplane patent, granted on 10 January 1907

- 1909. Knight originated – on paper – the stepped float

- July 1910. Gnosspelius designed and tested the first stepped float, at Windermere

- 25 November 1911. Waterbird was the first hydro-aeroplane with a stepped float to take off successfully and land with no damage, at Windermere

- 11 December 1911. Wakefield applied for the first stepped float patent, granted on 18 March 1913.

EXAMPLES OF AIRCRAFT WHICH USED STEPS

Supermarine S.6B racing seaplane, Boeing 314 flying boat, Consolidated Catalina flying boat, Slingsby Falcon 1 water glider flown from Windermere in 1943 by Cooper Pattinson and Wavell Wakefield and de Havilland Tiger Moth at Windermere in 1979.

In early Short Sunderland flying boats the hull step was abrupt, but on the Mark III it was a curve upwards from the forward hull line. The Mark III was the definitive Sunderland variant with 461 built, which included 35 assembled at White Cross Bay, Windermere between September 1942 and May 1944.

EXAMPLES OF BOATS WHICH USED A STEPPED HULL

The key difference for a boat is that there is no requirement to rotate; hence the use of multiple steps.

Thornycroft designed stepped hull racing boats from 1909, including Miranda IV in 1910 with a speed of 35 knots. Coastal Motor Boats (small, high speed, torpedo boats) for the Royal Navy, designed and built by him with the step added at the third skin, derived from these boats.

Linton Hope worked with Thornycroft. Hope later joined the Royal Naval Air Service and designed flying boats, with whom Windermere yacht designer Percy Crossley trained in Southampton. Hope was ‘much interested in the comparative problems provided by the racing yacht and the aeroplane’. – Flight magazine, 1 January 1910.

In a letter to Thornycroft dated 5 June 1915, his son remarked ‘Linton Hope was in this morning. He is now an Inspector of hydroplane floats for the Admiralty. He is very impressed with the Curtiss flying boat, which he has been up in recently, and says that it is practically the same as your Miranda hull when running on the water, touching under the centre of gravity just forward of the step, and more or less balancing on its tail.’

Maple Leaf IV. Built and designed by S. E. Saunders Ltd with 5 steps, the first boat to reach 50 knots. The British International Trophy was won in 1912 and 1913 when driven by famous aviator and America’s Cup yachtsman Tom Sopwith. Alliott Verdon Roe, who had built Waterbird as a landplane, bought a controlling interest in S. E. Saunders so leading to Saunders-Roe Ltd with speedboat and flying boat production. – See below under Miss England II.

Samuel Saunders invented a system of mahogany laminates sewn together with copper wire, applicable to the construction of boats and aeroplanes. This was patented under UK No. 222 of 1898 and No. 3640 of 1912, with the trade mark of ‘Consuta’. It was used in the hull of the Perry-Beadle flying boat which was unsuccessfully tested at Windermere in 1915 and broken up in 1916 at Cockshott.

Unnamed hydroplane. Used at Windermere so as to give student pilots practice in travelling fast over water and judging speeds, with a capability of 40 knots. The date of construction is not known, but it was in use during early 1915. The engine came from Gnosspelius No. 2 and the float from the Gnosspelius-Trotter.

Built by The British Power Boat Co Ltd in 1930, reached 55 mph at Windermere.

‘The arrangement of the steps was novel. The third step is not in line with the 2 further forward and at speed is not in contact with the water at all and this reduces the water friction still further. She represents the most sophisticated design of step hydroplanes.’ – White Lady II, Salvage and restoration, by Windermere Nautical Trust Ltd

Designed by Hubert Scott-Paine, who ‘saw the narrowness of the borderline between sailing and flying’. His company Supermarine Aviation Works Ltd built the racing seaplane designed by Reginald Mitchell (who later led the team which designed the Spitfire) which regained the Schneider Trophy in 1922 which had been won in 1914 by Howard Pixton. His company The British Marine Air Navigation Company Ltd combined with 3 other airlines to form Imperial Airways in 1924.

The decks and cowls were covered with aeroplane fabric for lightness. She flooded off Rawlinson Nab during a race on 20 June 1937, until salvage and restoration 45 years later. From 1930, Scott-Paine’s company The British Power Boat Co built fast motor boats for the Royal Air Force.

Miss England II. Built by Saunders-Roe Ltd in 1930, with 2 Rolls-Royce R aero engines, achieved 98.76 mph at Windermere on 13 June 1930. However, Sir Henry Segrave was killed following a capsize; in World War 1 he had been a fighter pilot.

Bluebird K3 – Filching Manor Motor Museum. Powerboat built by Saunders-Roe in 1937 for Sir Malcolm Campbell, with a Rolls-Royce R engine from the Bluebird car. The R-type engine had been developed for the Supermarine S.6.

Connections

The golden age of Windermere was from the late 19th century until the early 20th century and included the operation of steamboats and hydro-aeroplanes.

Scott-Paine was a personal friend of Roe. Roe and ‘Betty’ Carstairs were frequent visitors to Scott-Paine’s home. She won the 1926 Scratch Prize of Windermere Motor Boat Racing Club in Newg, becoming a member in 1928. Speed tests were carried out by her at Windermere in 1928 in Estelle I and Estelle II before she took the latter to the United States in an attempt to recapture the British International Trophy. In 1931, Scott-Paine competed in White Lady II, then named Whyteleaf III, against her for the Detroit News Trophy at Southampton.

Estelle I, Estelle II and Miss England II were all launched from the boatsheds of Borwick & Sons at Bowness-on-Windermere.

– Concerning flight from water, Edward Wakefield described it as ‘Something that beckoned’. – Aeromarine Origins by H F King.