BIRTH OF THE REPLICA

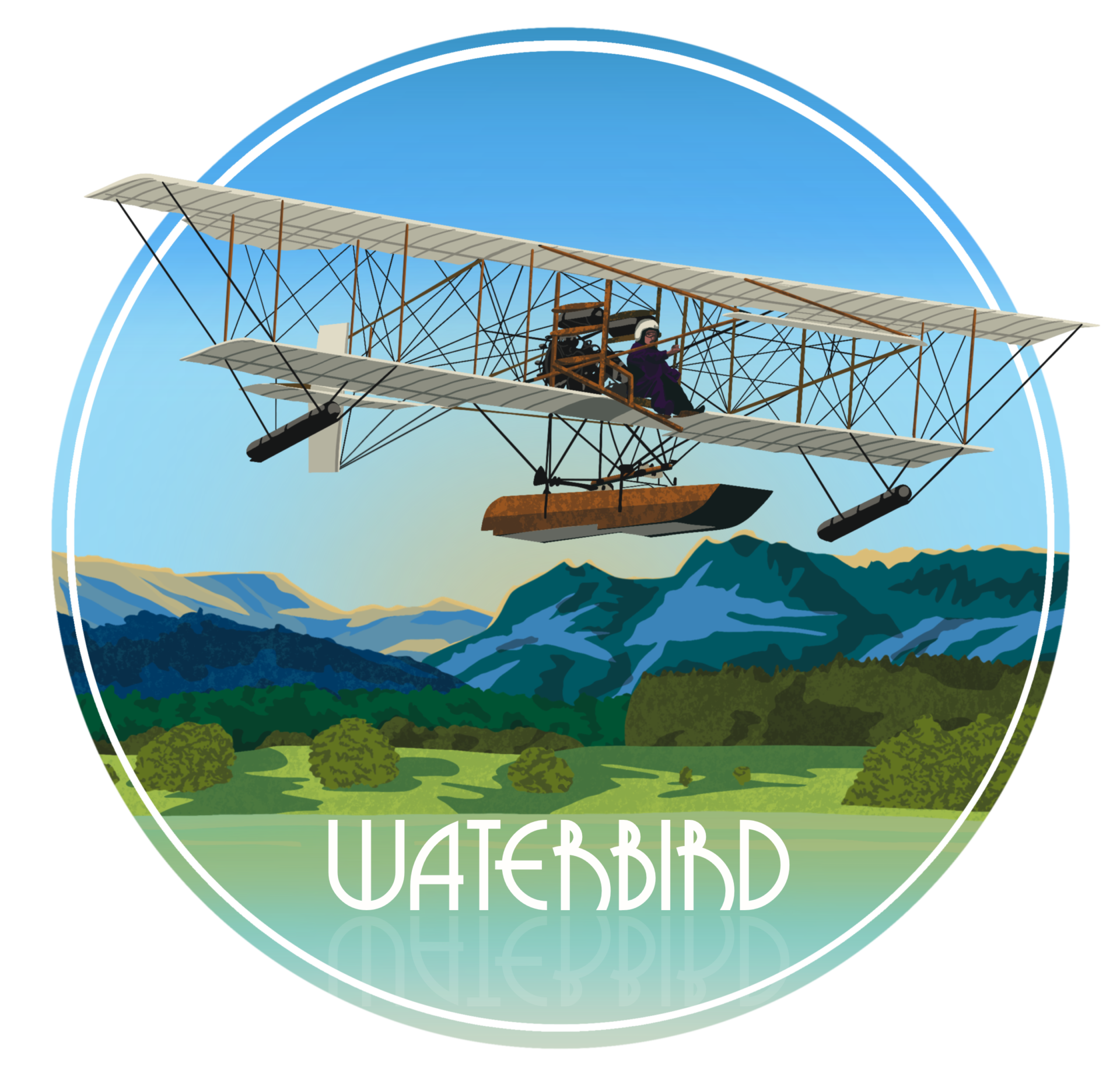

In 2010, The Lakes Flying Company Ltd commissioned Gerry Cooper at Vintage Skunk Works, Wickenby Airfield, near Lincoln to take on build of a replica of the Waterbird hydro-aeroplane, which had first flown on 25 November 1911 at Windermere. The challenge would be to construct an aeroplane that was faithful to the original, whilst it was determined which current regulations might be waived with what operating limitations.

A. V. Roe & Company‘s drawings and Specification from 1911, with inspection of surviving original parts then held at the RAF Museum Reserve Collection would form the basis of the project. Research was carried out at the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum, Hammondsport and the Smithsonian Institution, and also the 1912 book Practical Aeronautics was studied. Photos taken at Windermere in 1911 and 1912 were carefully scrutinised.

The wing spars were to be made of Douglas fir instead of the original spruce due to its higher strength properties, albeit weight would be slightly increased. Screws and modern adhesives would be used instead of nails. Modern Diatex wing fabric covering would be stitched in place instead of the original Pegamoid with tacks, despite the time penalty. Complementing up to date turnbuckles there would be certified bracing wires, to take advantage of metallurgical advancement.

It was initially decided that aluminium tubes would be used for the outriggers, as shown on this photo. However, following a visit to the Curtiss Museum by Gerry and stress tests by John Tempest for the Civil Aviation Authority, bamboo, which had been used for the original construction, proved to be as strong and totally adequate for the build. It was also found that ‘speckled inland’ bamboo was strongest and, this being the only aircraft using bamboo in construction, an item on the pilot’s pre-flight checklist had to include inspection of the bamboo for splitting.

Unusually, Waterbird had large ‘elephant’s ears’ inner ailerons on the top wings. As this was an original visual feature, it was decided that they would form part of the replica design; whether they serve any useful function aerodynamically would have to be determined when Waterbird was in flight.

As in 1911, Waterbird would be flown initially as a landplane with conversion to a floatplane being made only if the outcomes were satisfactory. There would then be one proving flight in the landplane configuration.

With materials sourced, plans ready, contract agreed and a green light from the CAA, the jig, on a 20 foot long table, was constructed in an industrial unit near the hangar. Mike Sales, a joiner, replied to an advertisement for a cabinet maker and found himself at Wickenby discussing the construction from minimal plans of a 1911 biplane. When Mike had recovered from the news that he was not required to build a cabinet, he agreed to work on the project saying “Turning pieces of wood into a finished structure and to see it work, especially off the water, is going to be a wonderful thing”. The skeletal framework of Waterbird was to be built using wood, and 60 ribs would need to be cut and shaped. Mike was employed to construct the centre section of the replica and 4 wings.

In 2011, with the framework of the biplane complete, the whole aeroplane was marked out on the floor of the hangar giving an indication as to the finished dimensions. It was also necessary to see how all the constructed parts would fit together. Meantime a visit had been made to Hill of Oaks, Windermere, where the original hangar had been built to see if there would be any possibility of trial flights from the same location on completion. From a historical point of view it would have added to the significance of the first flight of the replica, but it was soon discovered that the landscape, and Hill of Oaks, had changed beyond recognition over the last 100 years with trees to the water’s edge along most of the lakeside. It was decided that this would be impractical and, hopeful of an early completion of the project, other arrangements were made.

Back at Wickenby, work had proceeded as the framework of the centre section and wings was completed. Ian Gee and Adrian Legge, a retired naval officer who had joined The Lakes Flying Company Ltd’s trustees, arrived with Richard Raynsford who was a co-founder. Lt. (later Air Chief Marshal Sir) Arthur Longmore inspected and flew Waterbird on behalf of the Admiralty in 1912. His grandson, Tony Worth, and Tony’s son, Andrew Longmore, also came to see how the project was progressing.

More funds would be needed to continue with the build, and a TV crew joined the group at the hangar to share the story with viewers in the hope of finance being generated. However, significant monies were required to proceed and arrangements were made to put Waterbird into temporary storage. As the next elements involved fixing the engine bearers and constructing and positioning the pilot’s seat in front of the engine, construction was put on hold until 2014 when more resources had been found.

In 2015, John Tempest completed a loading analysis and it was thought that the replica could be put into ‘E Conditions’ Experimental category. This very detailed report made assessments of every part of the aeroplane including stress analysis of the wings, cross-bracing wires, struts between the wings, centre section and tail booms. Mathematical calculations were made and the centre of gravity estimated according to weight and balance. John’s assessment concluded that the construction should be elevated to meet modern standards. The project would now be supervised by the Light Aircraft Association.

Following a risk assessment, the LAA’s chief engineer Francis Donaldson visited the hangar at Wickenby. To say that the original 1911 Waterbird was a unique aeroplane/hydro-aeroplane is an understatement, but not only would the replica now stand alone in the world of airworthy vintage aircraft for its era, but also present challenges to the builders and inspectors alike. Staying true to the original design is complex, particularly since modifications were made in 1911 on a regular basis as a better way of doing things made sense. Waterbird made about 60 flights by 27 January 1912, so the team believed that this replica, with all the modern technical support available, should fly and still maintain the aesthetic impact of those Edwardian days.

Waterbird had operated using a 50hp Gnome rotary engine. Barely powerful enough at the time, it was decided to select a Rotec R2800. This seven-cylinder 2800cc radial engine would not be unlike the Gnome visually, but, with 110hp, would have 66% more thrust with improved fuel and electrical systems. This is the most significant deviation from the original. Whilst a Gnome engine is in production, it is the larger nine-cylinder version. The engine would have a conventional throttle control, rather than a ‘blip’ switch to cut the ignition, dual ignition, electric starter motor and a customised Hercules propeller. The engine was bought from the manufacturer in Australia and shipped to Wickenby.

The landplane had been built by Avro as an amended Curtiss design, where the pilot perched on a wooden seat with the engine close behind. Comfort was never intended, and the pilot also required a certain amount of agility to climb up into the seat without dislodging bracing wires. It was now Mike Sales who used his skills to construct a shaped seat to the 1911 dimensions as far as could be ascertained. The basic instrument dials were alongside the wooden rudder bar by the pilot’s feet, so good eyesight was needed to read the instruments and a wooden ‘stick’ would then control the outer ailerons and the canard. The original had no instruments fitted, but in the replica an airspeed indicator, RPM gauge and oil pressure gauge were installed. Subsequently, a combined exhaust gas temperature/cylinder head temperature gauge and a voltmeter were added. A fuel tank and an oil tank were positioned behind the pilot as he sat amidst a construction of wood, fabric and bamboo along with a network of wires. As with the whole build it was important to be true to the original as far as possible, but regulatory compliance had to be achieved before the aeroplane would be permitted to fly.

Gerry and his wife, Jenny, then set about covering the wings with fabric. The width of Waterbird’s upper wings had been extended at Brooklands by 9 feet and became 41 feet. There were 4 wings to cover and the fabric had to be measured, cut and laid over each wing before being glued, taped and then stretched. As Gerry used the tape and adhesive, Jenny hand-stitched the fabric to ensure it remained taut. This was in preparation for applying the 8 coats of dope [a lacquer used to tighten and stiffen the fabric].

When the wings were ready and the brackets in place, the moment of truth came as all hands were needed to fix the wings into place.. Turnbuckles tensioned the 200 metres of cable which would take the weight both when the replica was on the ground and in the air.

LIFT-OFF

It was always the plan to attach a temporary wheeled undercarriage to the replica before attempting any water trials. In 1911, the original Avro Curtiss-type aircraft had been taken down to Brooklands for test flights from the grass airfield to check that it would fly as a landplane.

Wickenby Airfield is ideal for a test flight, offering times when not otherwise in use and a grass runway. In 2015, Gerry climbed up to his seat ready for the replica’s first ground trial. Initial problems with the engine caused a delay and a further inspection was required before a ‘Permit to Test’ could be issued by the LAA.

When the inspection had been completed, a Permit was granted for a test flight. In June 2017, the authorisation arrived and the team prepared for a first flight. Also, exemption was granted by the CAA from displaying the registration G-WBRD.

In 2018, with perfect conditions and in view of the cameras, Gerry taxied out and Waterbird left the ground up to an altitude of 10 feet for short flights across the airfield. This photo is courtesy of Primetime Media Ltd with thanks to Steve White and Jo White. As he returned, having achieved the desired targets, the relief of the team and pride was evident on the faces of those who were fortunate to see the culmination of years of work. It was now time to convert Waterbird into a floatplane.

THE FLOAT

As the replica was coming together at Wickenby, a float designed and constructed by Richard and James Pierce of Ambleside had been brought over by Ian and Adrian together with a specially-designed trailer, which would be used for water launch and recovery. The float was designed, as far as possible, using measurements from the original. In 1971, surviving parts, including the original float, had been presented to the RAF Museum and they were used to help in the process.

In 1911, experiments were made using various sizes of floats for hydro-aeroplanes and although an aeroplane could float on the water outside the hangar it was another matter for it to depart as the pilot attempted to take off. Those who did take off, then found it was a further challenge to land on the water without capsizing!

Captain Edward Wakefield had Waterbird’s floats built by Borwick & Sons, boat builders of Bowness-on-Windermere. He decided that Waterbird’s float would need a ‘step’ underneath to encourage departure from water, and, having carried out trials when insufficient speed was still achieved, a second step was added towards the stern. Wakefield patented the stepped float, which was a world first. The replica float would need to sufficiently reduce the surface area in contact with the water and also allow the aeroplane to rotate for take-off.

Gerry started on the conversion, which included cutting the white oak keel beam and revising the steel tube frame to attach the float.

In order for Waterbird to be flown as a floatplane and because changes had been made to the structure, it was necessary for further tests and analysis to be made. 2 Cranfield University MSc students carried out research projects.

In 2020, the team took Waterbird to the National Water Sports Centre at Nottingham’s Holme Pierrepont Country Park for a first launch. It very quickly became apparent that there were serious problems, resulting in Waterbird being removed from the water before any damage was sustained. The test had shown that the float lacked reserve buoyancy.

This time, with the work at Wickenby completed, Waterbird was dismantled and taken by low loader to a new home at Liverpool John Lennon Airport.

FIXING THE FLOAT PROBLEM

Aeronautical engineer Dr. William Brooks now took on the role of ‘Competent Person’, responsible for the entire experimental test programme of the replica under the Civil Aviation Authority’s E Conditions. Boat builder Hamish Patterson from Hawkshead built the second floats, with Naval Architect Jack Gifford as designer. Naval Architect Prof. Paul Wrobel acted as The Lakes Flying Company Ltd’s overseer. The replica’s main float was now transformed with a 22 gauge aluminium floor like the original, 5 watertight compartments and increased buoyancy being 29% above that required by regulation, whilst the cylindrical wingtip floats have 3 watertight compartments.

Before any more trials were to take place, another detailed stress analysis had to be made and submitted to the LAA. John Wighton of Acroflight Ltd prepared the report.

WATER TRIALS

Permission was obtained from The Lake District National Park Authority, since there are Byelaws which prohibit exceeding 10 knots per hour on the lake and operating an aeroplane on it.

Facilities were kindly granted for a base at Grubbins Point from where water trials could take place. In June 2021, once again Waterbird was dismantled and carefully made ready for transport with the wings in a curtainsider and main section on a low loader. The trip of 100 miles from Liverpool was only the beginning of the challenging journey, as access to the western shore of Windermere is from a narrow road and then down a steep, rocky, winding track through a wooded area. There a scaffold hangar had been erected to house Waterbird for the duration of the trials.

As the team carefully unloaded the replica and prepared it for a night in the temporary hangar, a thorough inspection was performed to ensure no damage had been incurred during transit. Then, as following future delivery journeys, Bill Brooks carried out checks and rigging for flight.

THE PILOT

Pete Kynsey is a test pilot, well-known in aviation circles for flying and displaying warbirds, including Spitfires, at air shows. By contrast, his intricate aerobatic display flight in the diminutive Cosmic Wind, the ‘Ballerina’, is a masterpiece of sensitive flying. Pete’s flying career started with instructing and he moved on from helicopters, air taxis and private jets to airliners. He also enjoyed competition aerobatics and flying vintage aircraft. Ski flying in the high Alps is another interest, but currently Pete’s Aviat Husky on floats gave him the opportunity to instruct would-be seaplane pilots in the south of England. Pete was approached and asked if he would be happy to test-fly Waterbird and he readily agreed.

WINDERMERE

This was considered to be an opportunity to go on with the planned tasks, so very few people around Windermere were aware of the significant events at Grubbins Point. Supported by a rescue boat, Pete started the engine and taxied away from the shore. He gradually increased the power. There was relief that the replica was stable and accelerating.

However, pitch oscillations began at 25 knots water speed – best described as ‘porpoising’. Several attempts were made to attain take-off speed, but it was clear that all was not well. After discussion, it was decided to return Waterbird to Liverpool.

The recommended solutions to avoid entering a porpoising regime, were to reduce the angle of the steps and to increase the angle of attack between the float and airframe. To achieve the modification of a changeable angle, application to the LAA was granted for an adjustable frame to be fitted. In the event, it was not necessary to change the setting of the initial angle which had been calculated. The theoretical projection of the hydrodynamics was a take-off airspeed of 37 knots.

RETURN

In June 2022, Waterbird was returned to Grubbins Point. Pete is the ideal test pilot to be given the opportunity to make aviation history again on Windermere and the challenge of flying this replica of a 1911 hydro-aeroplane was irresistible….

Waterbird gathered speed, transitioning to flight without difficulty at the predicted 37 knots. The test programme was then accomplished without issue.

The rewards, following 12 years of dedicated effort, included a ‘Permit to Fly’, another aviation ‘first‘ for Windermere and the future opportunity to carry out public flying displays.

– ‘This machine is undoubtedly the first really successful hydro-plane in the country, and Mr. Wakefield and the manager of the company, Mr. Stanley Adams, deserve very great credit for the work they have done.’ – The Aeroplane magazine, 25 January 1912.

– ‘The effort to create in replica form the Lakes Flying Company’s Waterbird, Britain’s first successful ‘hydro-aeroplane’, and to emulate the 1911 original in flying it from Windermere has been among the most enthralling on the UK’s aviation heritage scene in recent years.’ – Ben Dunnell, Editor of The Aeroplane magazine, June 2023.