Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, OM, KG, CH, PC (1874 – 1965)

Reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown, London on behalf of the Broadwater Collection © Broadwater Collection

Click to enlarge image.

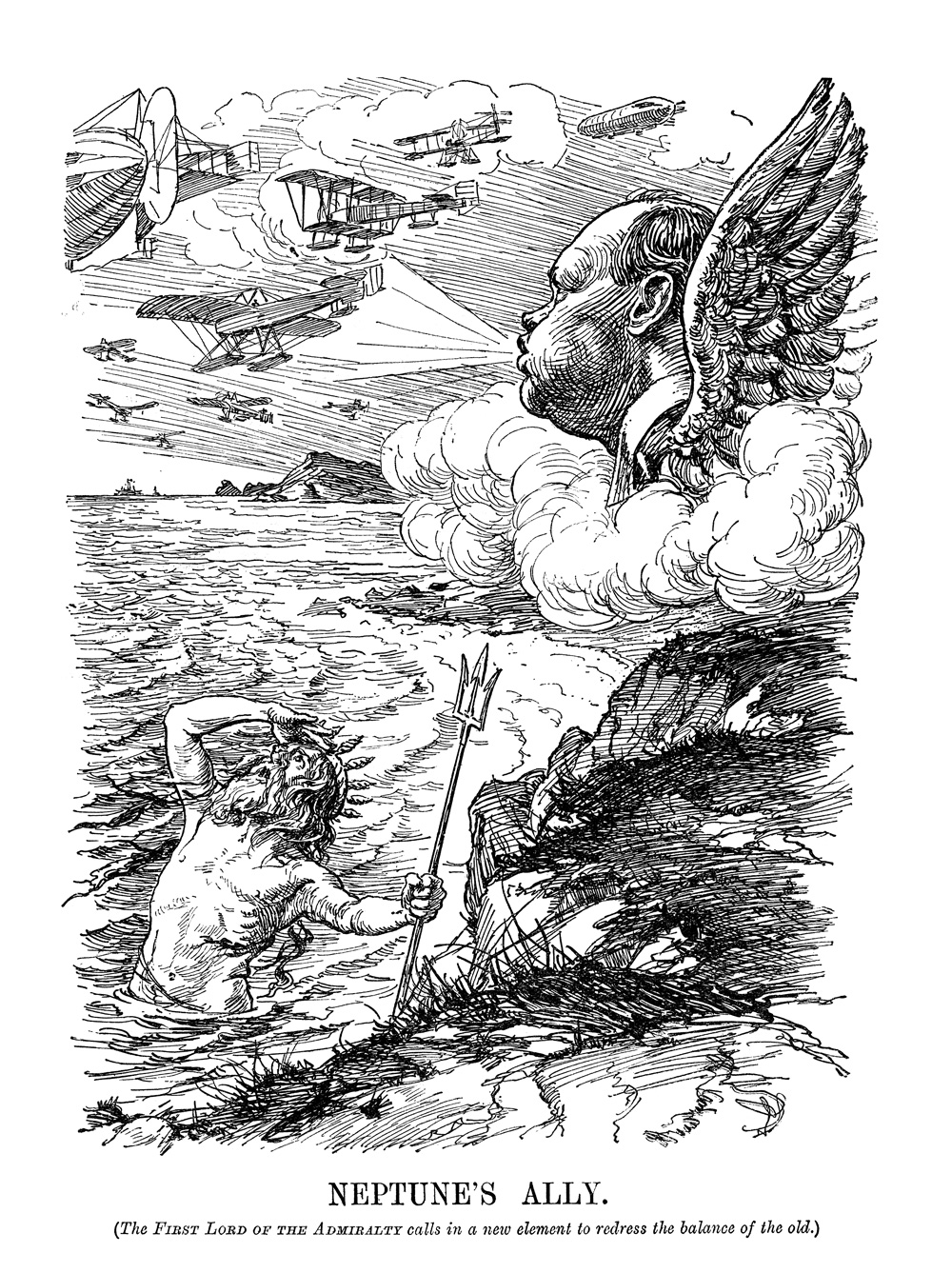

As First Lord of the Admiralty (1911-1915), Winston Churchill was a great supporter of ‘hydro-aeroplanes’, including confirmation of flying at Windermere

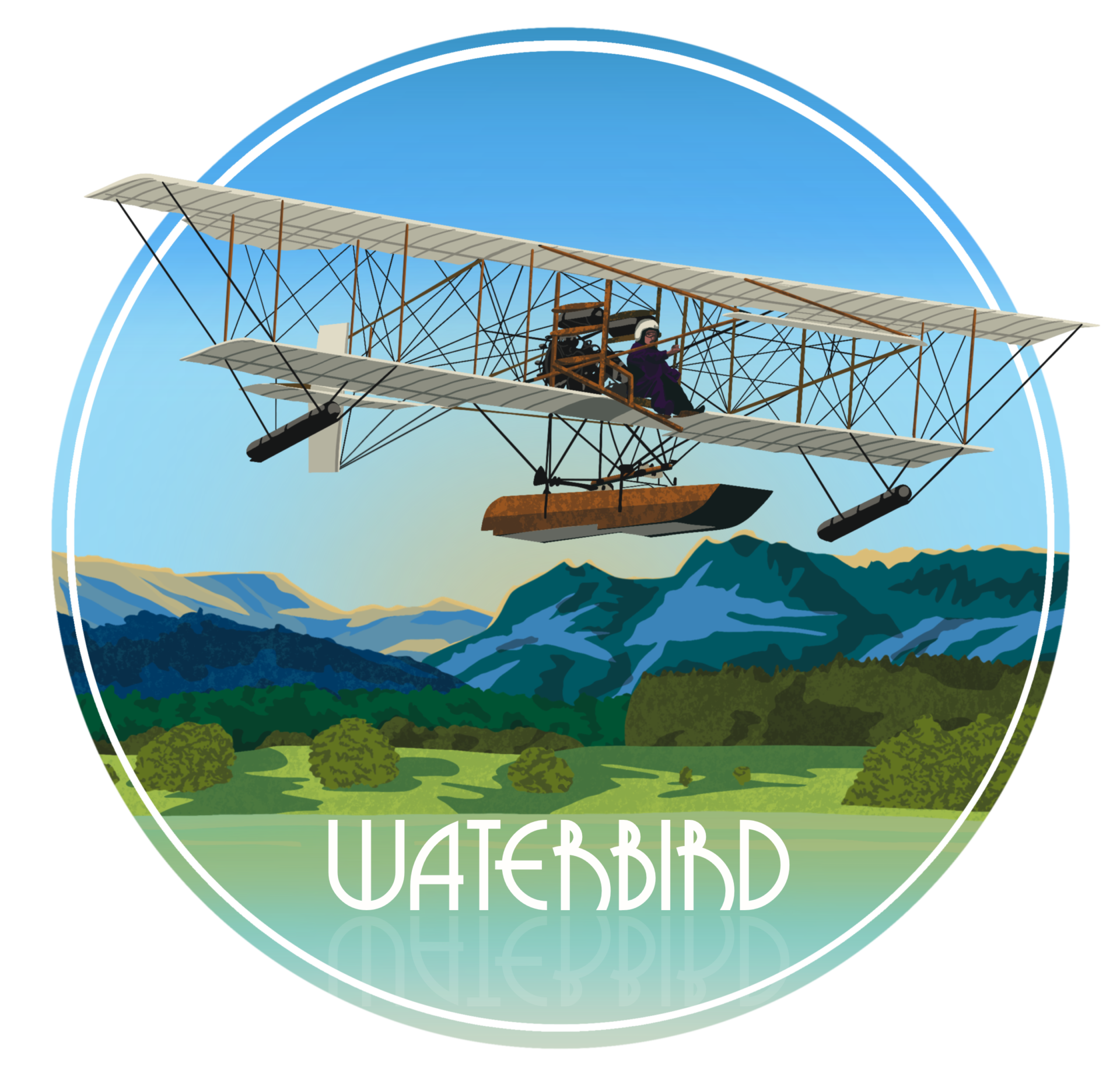

The hydro-aeroplane Waterbird was commissioned by Edward Wakefield and first flew from Windermere on 25 November 1911 with a ‘stepped‘ float. Waterbird had the distinction of being the first successful British hydro-aeroplane.

‘The importance of these facts in connection with harbour, estuary and coast defence and scouting need hardly be remarked upon. For the fame of Mr. Wakefield himself and Windermere it is to be hoped that the Admiralty may take the matter up so that we may not be left behind by any other European power.’ – Kendal Mercury and Times, 22 December 1911.

Private enterprise

In November 1911, the Standing Sub-Committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence was reconvened: ‘To consider future development of aerial navigation for naval and military purposes and the measures which might be taken to secure this country an efficient aerial service’. On 28 February 1912, the Report of its Technical Sub-Committee was approved, which recommended that the Naval Wing of the Flying Corps should be established and it attached importance to the maintenance of private enterprise in the field of aeronautics.

The Admiralty

Churchill was a member of the Standing Sub-Committee. Upon being asked in the House of Commons on 29 February 1912 about the Royal Navy and hydro-aeroplanes, he replied by referring to experiments, including at Windermere, and that “the results so far attained have been promising”.

Protesters against flying at Windermere wrote to the press and mounted a national campaign. They targeted the House of Commons with deputations and ultimately by having an MP raise a question on 16 April 1912. Wakefield had successfully quoted the Admiralty for his floats and undercarriages, or royalties, and to convert an Admiralty aeroplane into a hydro-aeroplane, but had not been able to advance this major counter-argument because he had signed the Official Secrets Act. Therefore, the future of flying at Windermere was hanging in the balance. – The answer at the top of this page came from Churchill, who stated that private hydro-aeroplane tests would continue at Windermere.

Churchill campaigned for an Air Department

Application for an Air Department was refused 3 times by the Treasury. Treasury sanction was then obtained and Captain (later Rear Admiral Sir, CB) Murray Sueter appointed as Director in November 1912. Churchill wrote Prince Louis of Battenberg, First Sea Lord, on 7 December 1912 ‘Captain Sueter requires supervision, and the connection between the Army and Navy work must be close and harmonious’.

Churchill took up a policy and a programme for seaplanes

‘A hydro-aeroplane or hydroplane as has floats instead of wheels, and skims along the surface of the water before rising or after descending, just as an ordinary aeroplane runs along the land’. – The Daily Mail, 21 February 1912.

The term ‘seaplane’ was coined by Churchill in the Commons on 17 July 1913 “We have decided to call the naval hydroplane a seaplane, and the ordinary aeroplane or school machine, which we use in the Navy, simply a plane, which is, I think, an effective method of description”.

In a Minute dated 26 October 1913, Churchill recommended 3 types of new aeroplane: an overseas fighting seaplane, to operate from a ship as base; a scouting seaplane, to work with the fleet at sea, and a home-service fighting aeroplane, to repel enemy aircraft.

In a Minute dated 21 December 1913, he called for radios to be fitted in seaplanes.

On 11 January 1912, a letter from Wakefield had been published in The Times and in Flight magazine in which he predicted scouting by hydro-aeroplane as being a ‘necessity for the safety of this island’. He envisaged the relaying back of information by a wireless installation.

Churchill advanced an argument in favour of seaplanes

In a Minute of 10 February 1914, Churchill wrote ‘The facilities of reconnaissance at sea, where hostile vessels can be sighted at enormous distances while the seaplane remains out of possible range, offer a far wider prospect even in the domain of information to seaplanes than to land aeroplanes, which would be continually brought under rifle and artillery fire from concealed positions on the ground, among trees, behind hedges, etc.’.

Taking lessons and flying as a passenger

Flying gave Churchill enthusiasm, understanding and foresight. Yet another example of his feeling for technical advances driving him onwards.

Churchill flew with Lieutenant Gilbert Wildman-Lushington at Eastchurch on 29 November 1913, so becoming the first cabinet minister in the world to assume control of an aeroplane in flight. – Flight magazine, 6 December 1913.

In February 1914, Churchill was flown in a seaplane at Portsmouth by Lieutenant Arthur Longmore, who had test-flown Waterbird for the Admiralty at Windermere on 20 January 1912, as he wanted to see for himself whether a submarine could be located when submerged.

He flew nearly 140 times, but relented under pressure from his wife Clementine and colleagues due to the risks, albeit he kept his foot in the door! A letter to his wife on 6 June 1914 included ‘I will not fly any more until at any rate you have recovered from your kitten: and by then or perhaps later the risks may have been greatly reduced’.

Churchill wrote on 10 February 1914 that ‘Seaplanes, when they carry torpedoes, may prove capable of playing a decisive part in operations against capital ships’. On 15 June 1914, he visited Longmore at Calshot and asked that the torpedo experiments be speeded up. On 28 July 1914, Longmore made the first torpedo drop by a British aircraft and pilot.

The following tributes say it all

‘The First Lord of the Admiralty has proved in a high degree the fairy godfather of naval aviation. The Navy hardly possesses a single type of aeroplane on which he has not made a flight as a passenger.’ – The Aeroplane magazine, 1 January 1914.

‘No Minister of our time has been at so much pains to become thoroughly acquainted with the work of his department as the present head of the Navy, with the result that probably no First Lord has at any period had so deep and thorough a knowledge of the work and needs of the Navy as Mr. Churchill.’ – Flight magazine, 26 June 1914.

‘The First Lord showed particular interest in all matters relating to the Naval Air Service and made many flights in aeroplanes and seaplanes. No occupant of this high office of state has made corresponding effort to acquire a practical knowledge of the work of the Navy.’ – Brassey’s Naval Annual, 1914.

‘Mr. Winston Churchill was always keen on aeroplane work, and the help and encouragement he had given to the Royal Naval Air Service ever since he took over the post of First Lord of the Admiralty were fully appreciated by all of us who were in a position to know. Without his keenness and driving power the RNAS would not have reached the state of advancement it had done in 1914.’ – Fights and Flights by Air Commodore Charles Samson.

Churchill’s faith in Wakefield and Windermere was borne out by the following events and gallantry of ex-pupils:-

- Wakefield converting an Admiralty Deperdussin aeroplane into a hydro-aeroplane, which flew at the lake during 11-25 July 1912

- an Admiralty representative visiting on 19 July 1912 to observe a new method of transmitting wireless messages from air to ground

- the award of an Admiralty contract for training pilots in December 1915. Large numbers of probationary Flight Sub-Lieutenants were sent there for basic instruction

- Charles Morrish and Henry Boswell being credited with the first sinking of a U-boat by the RNAS on 20 May 1917, for which they were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross

- becoming a Royal Naval Air Station from June 1916 until June 1917

- Charles McNicoll being awarded the Distinguished Service Cross on 22 June 1917 for convoy protection and combatting submarines

- former Waterbird pilot Herbert Stanley-Adams being awarded the Distinguished Service Cross on 1 October 1917 for reconnaissance and bombing flights in the Eastern Mediterranean

- John Hume being awarded the Distinguished Service Cross posthumously on 17 March 1918 for services in Mesopotamia

- Harold Gonyon and Victor Bessette being on the list of the first recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross on 3 June 1918, for respectively bombing a U-boat on 3 April 1918 and for services over the North Sea

- William Dickson taking part in the ‘most outstandingly successful carrier operation of the war’ on 19 July 1918, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order on 21 September 1918. Dickson was Director of Plans at the Air Ministry in 1941-2, working closely with Churchill. He became Marshal of the RAF.

Another record

In January 1942, Churchill made an 18-hour/3,330 miles journey from Bermuda to Plymouth aboard BOAC’s Boeing 314 Clipper flying boat Berwick, so setting another record by becoming the first world leader to make a transatlantic flight.

On 26-27 June 1942, he flew to the USA and back in twenty-seven hours in Boeing 314 Clipper Bristol. This photo was taken over Baltimore.

John Lankester Parker

John Parker was a pupil/instructor at Windermere 1915-1916. On 1 August 1928, Parker brought a Short Calcutta to the River Thames, setting it down between the Vauxhall and Lambeth bridges before mooring off the Albert Embankment. Amongst those who received a tour of the flying boat was Churchill, then Chancellor of the Exchequer. Following departure on 5 August, Parker just cleared Lambeth bridge and made a low pass over the terrace of the House of Commons.

– Churchill was the first peacetime Secretary of State for Air (1919-1921). As such, he signed Flight Lieutenant Wavell Wakefield‘s (Edward’s nephew) mention in the London Gazette on 3 June 1919 for gallant and distinguished service.